01 Nov Pricing Design Projects: Not a Game After All

Last week I had the pleasure of running one of the Graphic Artists Guild’s most popular events, The Pricing Game. The concept is simple, and it addresses a fundamental question for designers and illustrators: how do I know what to charge for my work? What strikes me every time I run the Pricing Game is that the answer, though difficult, is based on real factors. Pricing is an alchemy of experience, market forces, value, and a dose of realistic expectations.

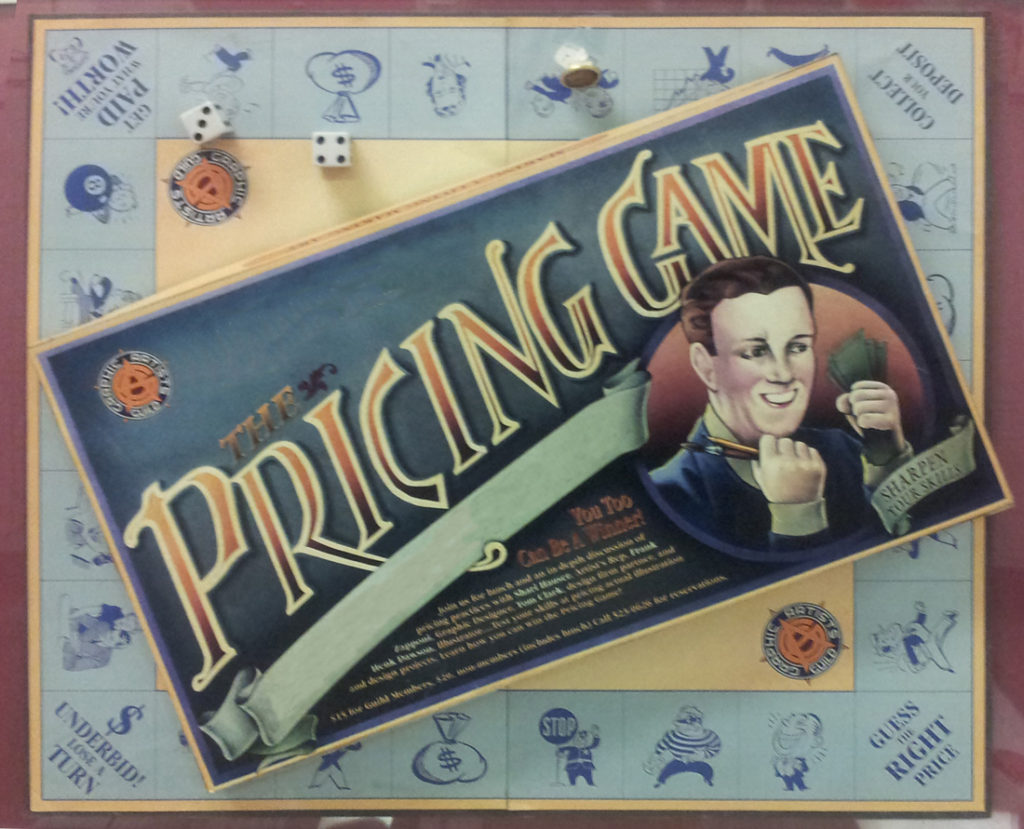

The Pricing Game in progress before a Guild National Board Meeting.

Photo © 2019 Michael Asirvadem

How the Pricing Game Works

The Pricing Game was developed in the Guild’s Seattle Chapter about 30 years ago. In the intervening years, the structure has been tweaked a bit, and I’ve run it as both a live event and as an interactive webinar. During the event, I’ll present three or four actual projects submitted by professional designers and illustrators. Attendees of the event – generally graphic artists at different levels of experience – are given the “specs” of each project – all the information they would typically gather from a potential client.

That includes:

- Type of project — brochure, illustration, logo, website, etc.

- Scope of project — 12-page 8.5x11 booklet, full color half-page illustration, logo consisting of client name and original icon, etc.

- Use of project — short print run distributed locally, appearing in national monthly publication, etc.

- Deliverable — what files and in what format, on what schedule

- Rights buyout* — is the client paying for a full-rights buyout or licensing the work, and on what terms

Pricing Game board illustration © Graphic Artists Guild

Another key bit of information the attendees are given is a profile of the client. Is the client a small mom-and-pop shop, a start-up business, or a large corporation? Is the contact someone who might be difficult to work with? Does the client expect to have an internal committee to review and weigh in on designs, or will there be one decision maker? Are there any other factors that give an indication that the review and approval process will consume a great deal of time?

After receiving the specs of a project, the attendees “bid” or shout out what price they would provide the client if they were to be hired to design or illustrate it. This is the fun part of the event. I’ll call on some of the attendees, typically people at the extreme ends of pricing, and ask them why their estimate was so high or low.

The answers provide some real insight into how the designers and illustrators adjust their pricing to arrive at that sweet spot of just the “right” price: one that reflects the value of the job, but isn’t out of reach for the potential client. Afterwards, I’ll reveal what the real designer or illustrator actually estimated and invoiced (and I’ll showcase the beautiful finished work).

The pricing spread provided by attendees can be extreme. I once ran the event at HOW Design Live, a large trade show for designers. When it came time to price a logo for a small shop, two attendees – Mr. $500 and Mr. $25,000 – got into a polite but intense debate about their pricing. Unsurprisingly, Mr. $500 was a designer working out of a small town in the Midwest, and Mr. $25,000 was a creative director at a large branding company in a major city.

So what is the “right” price? Stories like the one about Mr. $500 and Mr. $25,000 may lead clients to believe it’s all smoke and mirrors; we grab a price out of thin air and hope that the client will go for it. The truth is, pricing is based on real factors which are common to all designers. That’s definitely borne out by my experience in running The Pricing Game. Amusing outliers aside, the average prices quoted by attendees almost always fall quite close to the actual price estimated for the real project. Sometimes the average price is a bit higher or lower, but generally it’s fairly close.

So how does this happen – what is the alchemy that professionals use to bid on jobs?

The thing that everyone agrees on when pricing work is that the price must reflect two things: the actual cost the designer or illustrator incurs in running their business, and the value of the work to the client.

The Cost of Doing Business

That first is pretty easy to understand. Like every small business, designers and illustrators have expenses – rent, insurance, salaries, etc. – that need to be covered month-to-month. The Graphic Artists Guild instructs new professionals to approach pricing by first calculating what they need to earn in order to keep body and soul together, and a little extra to make life worthwhile. Usually, that translates to an idea of how much per hour the designer or illustrator needs to charge in order to keep the lights on. That serves as a guide to understand the minimum a designer or illustrator must charge for a project.

The second factor – the value of the work to the client – is harder to quantify. This is where experience is really helpful. However, for those without that experience, a bit of common sense can guide their thinking. For example, which is of greater value to a client: a flyer or a logo? A flyer is ephemeral – it’s generally handed out once, looked at, and discarded. By contrast, a logo is the most important graphic a client will ever purchase: it puts a “face” onto a business, and is the basis for a distinct and memorable visual identity. Clearly a logo has far higher value to the client, and the pricing should reflect that value.

The important thing to understand when talking about the value of the work to the client is that this value should not be based on the number of hours a designer or illustrator spends on a project (which is why most professionals refuse to give clients hourly rates). High-value design projects pull upon the intangible factors the designer or illustrator brings to the table: their experience, talent, communication skills, and empathy. None of these factors can be quantified into a simple equation.

We’re Not Widget Manufacturers

This all speaks to the devaluation of professional standards that crowd-sourcing and logo mills engage in. Businesses that promise a logo for a set fee ($200? $500?) or by having designers “compete” in producing a “winning” design reduce design to a commodity, as if designers and illustrators are widget-makers on a production line. Tricia McKiernan, former Executive Director of the Graphic Artists Guild, said it most eloquently:

“Crowd-sourcing may be legal as a business model, but it is another form of spec work taken to an extreme, and far from ethical from the Guild’s perspective. We’re talking about devaluing the work of an entire profession in an incredibly public fashion. Crowd-sourcing sites encourage below-market rates and treat graphic artists as an expendable commodity instead of highly trained professionals providing a genuine service.”

So what is the takeaway for clients and anyone looking to hire a graphic designer or illustrator? If anything, I hope there is an understanding of the diligence and thought that goes into our pricing. We don’t just consider what works for us, and throw out the highest price possible, hoping a client will fall for it. We base our pricing on what we need to earn to survive (and hopefully thrive). With the goal of not undercutting our market, we take into account what other professionals are charging, based on discussions with our peers, our Pricing Games, and the Graphic Artists Guild Handbook: Pricing and Ethical Guidelines. And lastly and most importantly, we consider our clients – what they need, what challenges they’re facing, and how we can deliver to them, affordably and fairly, the best solution.

* In an all-rights buyout, the client purchases the right to use and reuse the project, in any medium, any number of times, for an unlimited time. Typically clients will purchase the rights to a company logo as an all-rights buyout.

Rebecca’s headshot © 2016 Caroline Kessler